Why should you care how much money I make, so long as you are happy?

Ben Shapiro

With this quip, Shapiro artfully elides the key issues of inequality. It minimizes the genuine burdens, limits, and precarity—intolerable to the rich—of poverty (plenty of poor people are happy, yeah?). It assumes merit and assumes away fairness arguments on income (he “makes” it; the legal system that protects the making and saving is assumed away; and surely everyone gets what they deserve, right?). It turns discussion to income and away from wealth, which is where inequality is both most meaningful and most the result of law. “Money” is a socially created and socially protected claim on real resources. Assets, financial and real, are legally protected ownership of real resources and financial arrangements (real estate, insurance, financial assets). Not only does Shapiro benefit from such things as copyright enforcement for his income. Anything we own or save beyond what real goods we have on hand hinges on money and law. Without money there would be no way to have claims on real resources beyond what we have on hand; without legal protection we could own no more than we could protect ourselves.

Used fairly, money and property rights provide individual and social benefits (we aren’t in the forest fighting over ownership of fallen fruit; with money we can defer consumption in ways impossible without it – imagine trying to preserve enough food for retirement). The philosophy of property rights justifies ownership laws because they reduce conflict, and justifies a system of saving claims on deferred consumption (via “money”) for security and retirement. Protection of claims that become so large and unequal (often the result of gaming the system) as to do more social harm than good has no functional purpose, and therefore no philosophical justification.

Quips vs. Real Life

[For some data the most recent figures are from 2018; to make figures comparable I use mostly 2018 data]

The 2021 household poverty line for a US couple is $17,420.1 That’s $23.86 per person per day. And of course, this $47.72 per couple isn’t for just daily meals and entertainment, but must cover housing, furniture, utility bills, internet/phone/cable bills, transport, possibly auto insurance and gas, medical expenses or insurance, work clothes etc.

For a household of one, it is $35.29 a day (for an idea of how it scales: for an 8 person household of 2 adults/6 non-adults, it is about $14.50 a day per person).1 In 2018, 38.1 million people—11.8% of the population—lived at or below the poverty level.2 About thirty percent of the population lives at or below double the poverty level—$47.72 a day per person in a 2 person household or $70.58 a day for someone living alone.

Merit

The top one percent in 2018 (US) earned on average $2,021 dollars a day. An individual at the very “top” of the poverty level earned $33.26 a day, an almost 61 fold difference.

Does a person in finance work 61 times harder than a service worker? A “frontline” worker? Do they provide 61 times more social benefit? A large part of high income is from finance and legal services (at least some of both of these of questionable social benefit and sometimes doing outright harm to the real economy) and management (again, the rise in management positions, such as in higher education, are of questionable benefit). Legal and financial services also have restricted entry, increasing their income.3 It’s true that significant portion of high income earners are in the medical field, one area of unquestionable social benefit, and that demands extreme skill. At least in the US, a significant reason for very high incomes in the medical field is unnecessarily restrictive licensing,4 and while certainly deserving high compensation, even this skill may be overcompensated, and its social benefit attenuated if, as in the US, it is priced out of reach of many. Other high incomes are at least in part due to legal arrangements/protection, and/or political influence: oligopoly (“big tech,” pharmaceuticals), oligopsony (agriculture, publishing), and copyright law (media/entertainment). This is not necessarily to say these are wrong, especially the latter; however, allowing high levels of profit in the former is a political/legal choice, and although society may decide copyright protection is overall beneficial, it is clearly a social choice which allows high incomes from media. Once wealth is acquired, further income is often gained due purely to legally protected financial arrangements of asset ownership. Conversely, low income jobs are in part due to suppression of minimum wage laws and unions. Much income differential is due not to merit, but political choices and the power to control these.

Especially evident during covid, there are good reasons to suspect that low paid service jobs, agricultural, warehouse, transport and logistics jobs, and “frontline workers” do not receive fair compensation when we consider the claims on real resources their income allows compared to the real social benefit from their work. Arguments on “merit” for the high incomes in finance and other restricted-entry and legally protected ways to earn income compared to these worker’s incomes do not seem convincing. We choose, as a society, to protect and encourage high incomes in some fields and not others.

Motivation

When we talk about attempts to increase income, a change from a (2018) daily income of $433 (top 10% minus the top 1% extreme, which was $2,021 a day) to $466 is barely noticeable. But $33 a day doubled the income of someone at the top of the poverty line, a life-changing increase. That’s where your “motivation” is, and often where significant increases in income are hardest to achieve through smart, hard work.

An aside: In a world where household incomes are $641 a day (mean for top 20%), and your household lives on $37.74 a day (mean for bottom 20% of households), much of the world is effectively cut off from you. And that is not even considering wealth differentials, which are much wider (below).

Do we need extreme incomes to encourage entrepreneurship and economic dynamism? Ireland, Norway, and Germany all have higher labor productivity than the US5 but more income equality. Switzerland and Sweden are higher in income equality than the US, and both rank higher on the Global Innovation Index.6 Income inequality is not a necessary factor for a dynamic and productive economy.

The average wage for the “lower” 90 percent of the population in 2018 was $37,574, or $102.95 a day. Ask yourself: If a person can make double the average for 90% of people, is that not motivation? Triple? ($308.85 a day). We now (2018 figures but little changed) have a spread between a poverty line of $33.26 a day and incomes of $2,021.09 to $7,693.44 a day (top 1 and .01 percent). Clustering around the median would mean a vast increase in quality of life for many, and more social cohesion and less political influence from an extreme high. And as research has shown, inequality itself is a public bad,7, 8 even for the wealthy (not only living in a less healthy, less happy society, but one with less social cohesion, “social contract” legitimacy, and more, as The Economist notes, fear – “The stark relationship between income inequality and crime: Both theory and data suggest that if you’ve got it, don’t flaunt it,” 2018).

There is, of course, the question of investment in time, money, and effort in high-skill jobs. But then we should be looking at why we, as a society, do not invest in the education and training for jobs that require long years of specialized training. We need scientists, doctors, bankers, managers, and lawyers. By organizing (that is, paying for) the long-term investment in time and effort of those willing and able to acquire such specialized skills, we make these careers more meritocratic while taking the risk away for individuals dedicating time to acquire the needed skills (some fail, which should be fine, not a life changing setback with debt). The opportunity for all to pursue highly skilled jobs provides true motivation and merit.

But these income differences are not what really divides us.

Wealth and Debt

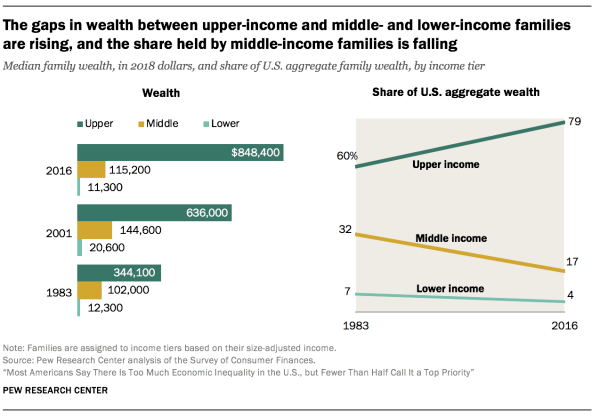

Comparing incomes hides the real divide: wealth. Below (left) is the median wealth of upper, middle and lower class in the U.S., and (right) the share of wealth and trend.

“As of 2016, upper-income families had 7.4 times as much wealth as middle-income families and 75 times as much wealth as lower-income families. These ratios are up from 3.4 and 28 in 1983, respectively.”9

Low income households are generally living only off the income mentioned above—and often with debt that is virtually unavoidable on low incomes—renting cheap housing (take that as you want) at the maximum they can afford, often with low job security, and with no (nor any hope for) accumulated wealth, and thus not only job insecurity but permanent financial insecurity.

The wealthy, on the other hand, often live on passive financial income streams (imagine what a service worker thinks of the concept “passive income”) which are purely the result of law, often tax-protected, in much more valuable housing (i.e., larger, nicer, safer) that represents a much higher asset if needed, all of which afford vastly more financial security.

In other words, $47.72 a day each for a low-income couple is not only difficult to live on, it is just that amount, with little hope of the amount changing significantly, and a lost job or medical emergency away from disaster. The top ten percent minus the 1 percent extreme still average $433 a day,10 often in part through passive income, and with a large amount of accumulated wealth to fall back on. A job loss or medical or similar emergency has little chance of making them financially insecure. On top of large wealth cushion, they can afford high quality insurance, and have plenty of options to monetize assets if needed.

To give an idea of the scale of accumulated wealth, consider that there is a fight to put a cap on tax-free retirement accounts at $20 million. These can be accessed tax free at 59.5 years. With an average lifespan of about 79.5, that’s $2,740 a day for 20 years even with zero work income.

Because the wealthy and poor often cluster together, looking at counties can highlight differences in asset wealth:

Income from assets— like stocks, rental properties and interest — now makes up one-fifth of total personal income in the U.S. Yet most Americans have few assets besides their primary residence and retirement account, and even those are usually out of reach for low-income workers…Between 1969 and 1990, the gap between the top and the bottom U.S. counties by average asset income doubled — and then increased sixfold between 1990 and 2019.

Mapping the Gaping Disparities in Income from Assets 11

Any way you look at it, there is a vast and growing wealth divide in the US. And it is wealth, not income, that matters for financial security, daily life, and political influence.

Debt

Debt doesn’t mean the same thing for the wealthy and the poor. There is the obvious way that the poor often must go into debt and struggle to pay it off, while the wealthy generally can easily pay debts they choose to take on. Debt by the poor is a struggle to live a “middle class” lifestyle, while for the rich it is strategy: investment, tax, business, and finance opportunity. In some cases, the wealthy live off debt on purpose in ways that are not remotely possible for the poor. (The wealthy not only have assets for collateral, they also receive lower interest loans).

As example, consider the so-called “buy, borrow, die” strategy. High income earners put their excess in assets, which are not taxed until sold, building up assets tax free. They then “can borrow against those assets at an interest rate that’s much lower than the rate at which the assets will appreciate over time…and use those funds as spending money. But unlike the wages and salary most people use to pay for living expenses, the borrowing isn’t taxed, so they face a relatively low tax bill. Once they die, the assets pass to their descendants tax-free or with minimal tax treatment.”12

Compare that type of debt to those making less than $96 a day, who had credit card debt of on average $3,830.13 That is $10.50 less a day to live on if they tried to pay back just the principal in a year. They likely have higher interest rates than the wealthy as well, but even without interest that would effectively put them at $85.50 a day. And that’s not including all other debt – mortgage, student loan, medical, auto and other.

The wealthy pay for advice on how to use Roth IRAs, SEP IRAs, 529 plans, GRATs, use “buy borrow die” loans, and many other means of shielding and amplifying their ownership of wealth.14

The poor simply can’t participate in these financial strategies of the wealthy. They often don’t have enough wealth to even participate in the banking system at all. In 2020, 37 percent of those making under $25,000 a year were either unbanked (16%) or underbanked (21%, the latter defined as relying on such services as check cashing services, payday loans, pawn shop loans, and auto title loans to scrape by). Virtually all of the unbanked (94 percent) had income below $50,000. Almost half of credit applicants with income below $50,000 were denied credit or approved for less than requested.15

Loans for the poor and the rich are qualitatively different. The former a matter of survival and their repayment a distress, the latter a matter of comfort or finance and repayment a matter of course.

These disparities are not needed to motivate, are in no conceivable world fair when it is society itself that protects the assets of the wealthy. The poor are not “happy” that they must struggle to meet basic needs or precariously hold on to often unrewarding jobs and a “middle class” standard of living while law alone protects the claims on real resources that allow the wealthy to live on passive income, not worry about the precarity of the daily lives of millions, pollute far more than average, and manipulate laws to maintain and further this outcome.

The sentence in Ben Shapiro’s book preceding the title quote is this: “Discussions of income inequality, after all, aren’t about prosperity but about petty spite.”

I’m sorry Mr. Shapiro, but this is entirely about prosperity. And not at all petty.

The souls of the people

The most fatal ailment

Ill fares the land

So long as you are happy

What we yearn to be

The sane and beautiful

The sum of what we have been

A little world made cunningly

Like a sinking star

The cries of the harvesters

The earth with its starkness

Written in blood

To do and die

In this fateful hour

So that we may fear less

The rags of time

References

Photo: Dorothea Lange, Library of Congress

Ben Shapiro quotes are from And We All Fall Down (2018), p. 6.

[1] US Department of Health and Human Services 2021 Poverty Guidelines

[2] Poverty USA (Catholic Campaign for Human Development, CCHD)

[3] Make elites compete: Why the 1% earn so much and what to do about it. 2016. Brookings.

[4] U.S. Health Care Licensing: Pervasive, Expensive, and Restrictive. 2020. Niskanen Center.

[5] https://blogs-images.forbes.com/niallmccarthy/files/2019/02/20190205_Labor_Productivity.jpg

[6] https://www.wipo.int/global_innovation_index/en/2020/

[7] Does income inequality cause health and social problems? 2011. Joseph Rowntree Foundation. https://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/default/files/jrf/migrated/files/inequality-income-social-problems-full.pdf

[8] Income Inequality and Happiness: An Inverted U-Shaped Curve. 2017. Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5705943/

[9] https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/01/09/trends-in-income-and-wealth-inequality/

[10] Economic Policy Institute

[12] How the wealthy use debt ‘as a tool to screw the government and everybody else’. 2021. Market Watch.

[13] Debt.org. May 26, 2021.

[14] Information on these is easily available online. Just one example https://www.forbes.com/sites/jrose/2018/07/17/the-1-account-all-wealthy-people-have-that-you-probably-dont/

[15] Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2020 – May 2021. Federal Reserve.

Hi Clint,

As an immigrant to the USA myself, I wonder if these countries are so wonderful:

“… Ireland, Norway, and Germany all have higher labor productivity than the US5 but more income equality. Switzerland and Sweden are higher in income equality than the US, and both rank higher on the Global Innovation Index….”

…where are the tens (or hundreds) of thousands of people on their borders clambering to gain access to those countries, like we currently have along our southern border?

Hell, even when immigrants make it to France, they pile up in awful temporary shelters in Calais just to try to sneak across the Channel to the fascist, unequal, immigrant-hating, Tory-ruled UK! Why do they do that if life is so much better in the warm and fuzzy and equal Eurozone? Something doesn’t make sense.

Cheers, Bruce

LikeLiked by 1 person

Off the top of my head: Don’t border Latin America, and certainly not a huge single border as the US has; Europe is fairly strict in Med, multiple land borders must be crossed from the southeast of Europe to access those countries; Norway and Germany have relatively difficult languages, certainly not the modern lingua franca as the US (and UK) does; Norway and Ireland are small, not so easy to dissapear into (once in the US, you have access to a huge physical area and huge economy) and by sheer size (population, land, economy) don’t offer as many niches to slot into; Norway and Ireland physically restricted on entry possibilities, surely 1) more expensive to get to and 2) relatively easy for them to restrict entry. Norway crazy expensive just to eat also. Not to mention the make-up of US population makes cultural assimilation easier for many immigrant groups – there are large communities (and chain migration to these) of many immigrant cultures in the US, pretty much from forever. I haven’t checked lately, but immigration to Germany from Turkey, for example, was high; percentage wise, think Norway has fair bit?

Also, you imply not many stay in continental Europe – but I would want to see stats for all of Europe against US. Also, from my experience, no one lives in EU countries easily without proper papers as far as work, ownership, licenses etc. Good or bad, it certainly would make it difficult for anyone to live/work in the EU without papers; I’d say much more so than in the US.

Just off the top of my head – Cheers, Clint

LikeLiked by 1 person